Draper to Build on its Biosecurity Tool Development for IARPA

CAMBRIDGE, MA—Advances in gene editing technology and improved access via the web have substantially increased the prevalence of engineered organisms in our world. Benefits range from pest-free crops to reduction in the spread of infectious diseases, but along with these advantages comes a need to identify good bioengineering from the kind that might pose a threat.

To address this challenge, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) has contracted with Draper to develop new kinds of detection systems that can identify whether engineered organisms have been created from natural organisms. Officials at ODNI’s Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) have awarded Draper a two-year Phase 2 contract under its Finding Engineering-Linked Indicators (FELIX) program, for a total contract value worth $7.8 million.

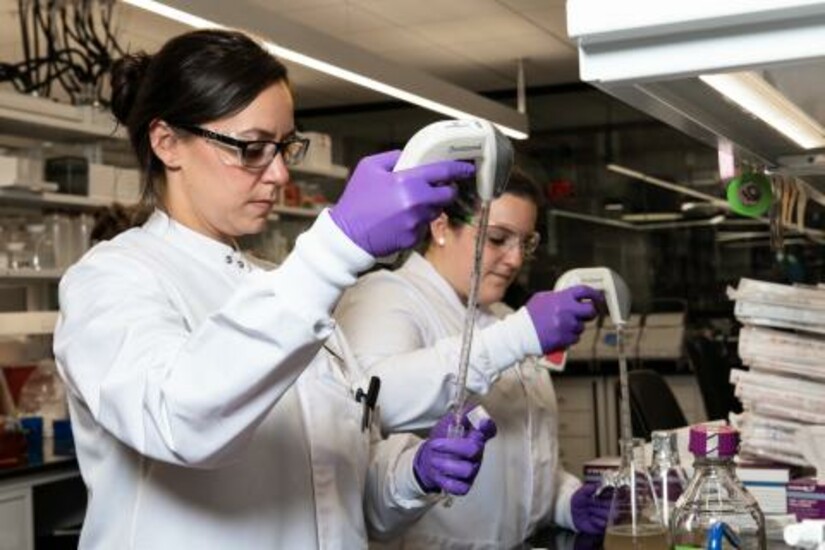

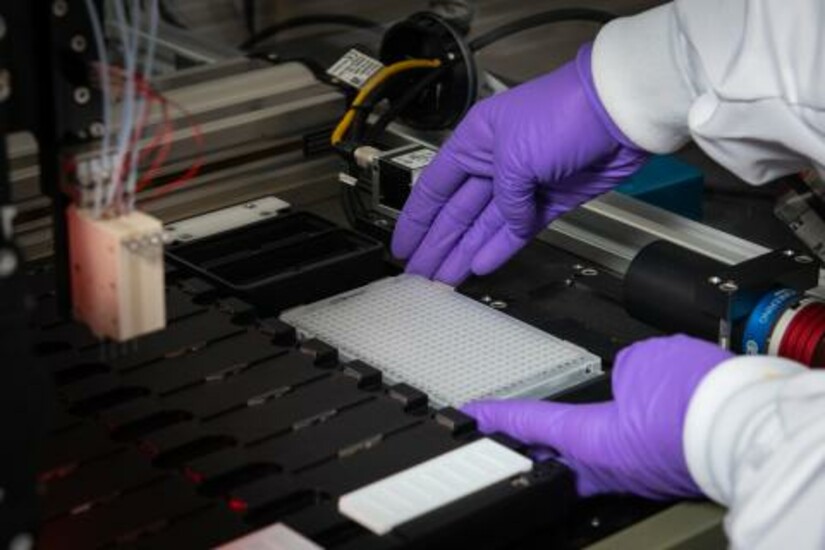

The award calls for Draper to continue development of two distinct lab-based genetic tests, custom bioinformatics pipelines that contextualize DNA sequencing data and miniaturized microarray hardware with a specialized design. The device—smaller than a postage stamp—allows multiple rounds of genetic tests on any organism, from a broad variety of sources including soil and water. Potential applications include biothreat detection, environmental monitoring and food inspection.

The microarray can be equipped with up to 10,000 surface probes to help identify genetic engineering. The device and associated lab methods combined are sensitive enough to pick out a ratio of a single engineered organism against a complex environmental background containing millions of natural organisms—a signal-to-noise ratio that is a significant improvement over current methods.

Kirsty McFarland, molecular microbiologist and Principal Investigator on Draper’s FELIX program, says the technologies under development will be able to detect genetic signatures that are not accessible with current technologies. “Current methods for detecting engineered organisms, in soil for example, read only a subset of all the genetic material that’s present in the sample, typically through next-generation sequencing. That process inherently misses information and does not reveal important genetic context,” she said. She noted that one gram of soil may contain up to one billion microbial genomes.

To accompany each genetic identification system, Draper also developed two custom bioinformatics tools, which include a computational pipeline and visual dashboard that convert lab data into actionable intelligence that users can see on a computer screen.

Draper’s FELIX contract is the result of close collaboration between the Synthetic Biology group and Draper’s Special Programs Office.

Released July 28, 2020