Take a Test Drive on the Moon

Before piloting a spacecraft, astronauts spend countless hours in flight simulators running through scenarios for normal operations, unusual events, and emergencies.

As NASA prepares to send astronauts back to the moon with new rovers, the engineers supporting them will need a similar system to practice driving on the lunar surface.

So Draper built one.

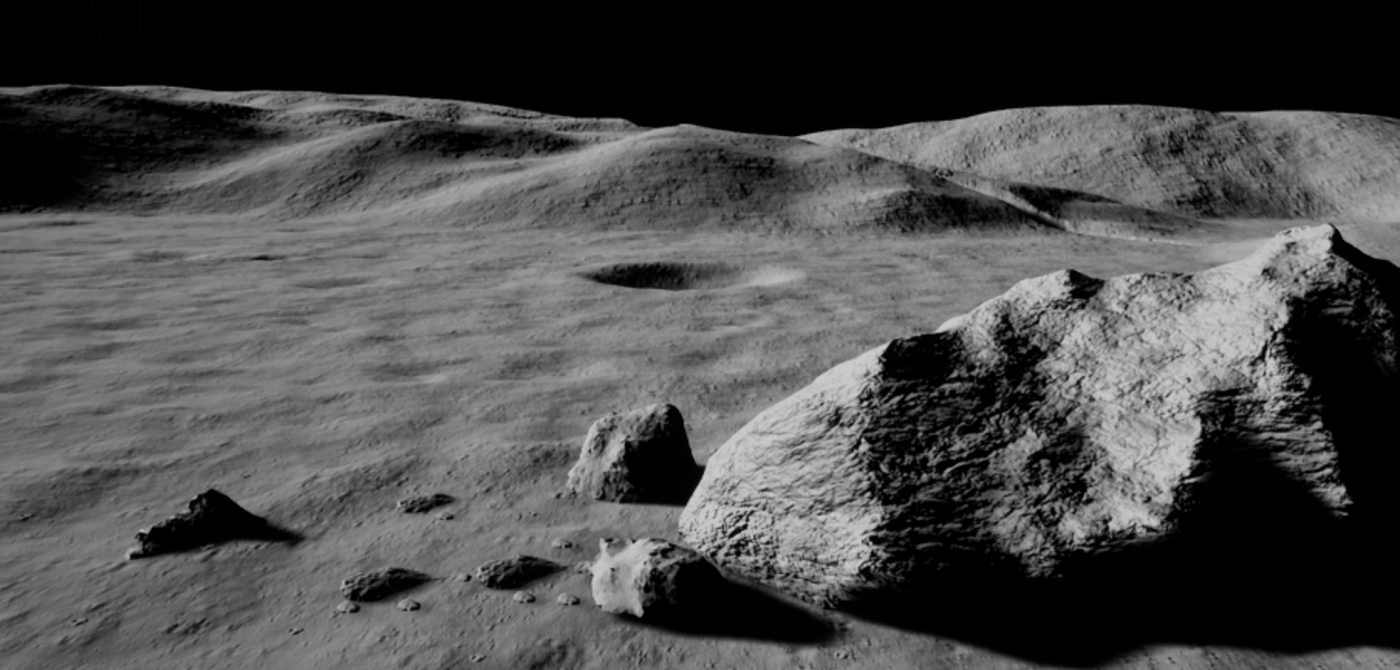

Our engineers developed a photorealistic simulation of the moon’s terrain – including rocks and boulders, elevation changes, and lighting conditions.

“It’s pretty cool that you can pilot a vehicle within this environment while seeing something akin to what astronauts might see someday,” said Mitchell Hebert, senior autonomy engineer.

What makes Draper’s simulator special

Most simulators are based on real data that represents known features. For example, flight simulators can reproduce wind and atmospheric conditions, and racing simulators recreate tracks down to tiny bumps in the pavement. It’s relatively easy to replicate features on Earth, where specific data can be readily collected.

That’s not the case on the moon.

In total, humans have spent just over three Earth days exploring the moon. Researchers have almost no actual data about the textures and shapes of its surface.

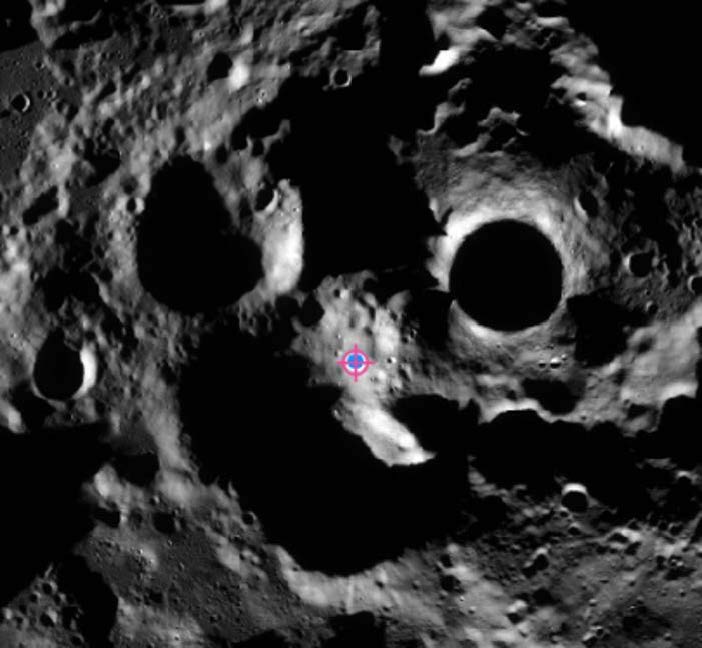

Nearly all the information we have on the moon’s surface comes from satellite imagery, which lacks the perspective and resolution generally needed to create accurate 3-D renderings.

To simulate lunar terrain, our engineers began with satellite images and elevation models of the lunar South Pole, a key landing site for upcoming Artemis missions. We combined a commercial drone simulator with our proprietary framework and algorithms for detecting hazards, adapting the system to simulate the physics of a ground vehicle. And we integrated open source rover models and a commercial simulation engine that allows for precise control of lighting conditions.

The result: a realistic model of the lunar environment that can serve as a high-fidelity simulation test bed for future rovers.

“It takes a strong understanding of satellite imagery to develop a simulation of this high fidelity,” said Hebert. “Which made Draper an excellent candidate to develop it.”

One-of-a-kind Test Bed for Vehicles and Algorithms

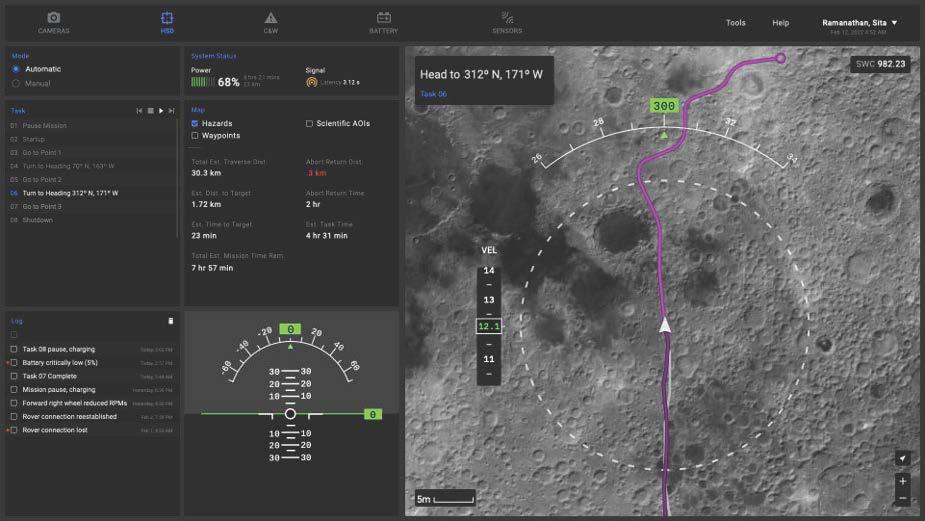

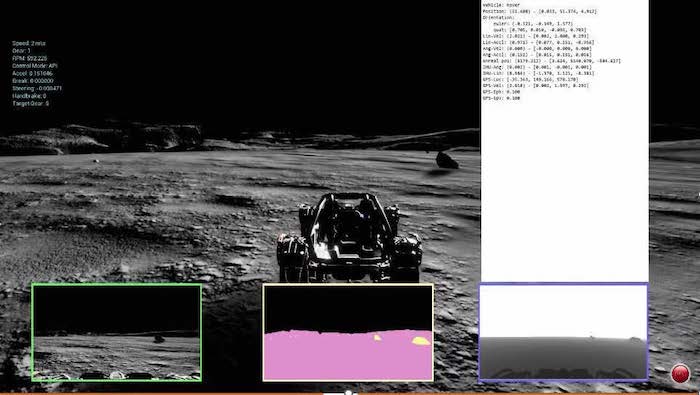

Draper is the first to announce development of a simulator designed for the technologies it will take to develop and test lunar terrain vehicles (LTVs) and the systems that enable them to navigate and perform missions autonomously.

Our engineers have developed a variety of autonomous navigation systems for Earth-based aerial, ground, and underwater missions.

While those systems can be field tested, our autonomous LTV navigation system cannot.

The lunar simulator is allowing us to validate and refine the algorithms that power this system, studying issues specifically related to detecting hazards and navigating in GPS-denied areas. It also supports development of our mission manager algorithm and controls, which allow humans to override the autonomous system as necessary.

Draper’s contributions to U.S. lunar exploration dates back to the original Apollo missions, and our support for the Artemis Program includes design and development of instruments and software that will power the Orion capsule, Space Launch System rocket, Gateway orbital outpost, and Human Landing System spacecraft. We are also leading the development of an autonomous vehicle for delivering science payloads.

So when NASA or any commercial rover team calls, we’ll be happy to let them take a spin around the moon.